- February 22, 2026

Legal Standing for Rocks: Necessity for an Indian Eco-centric Framework

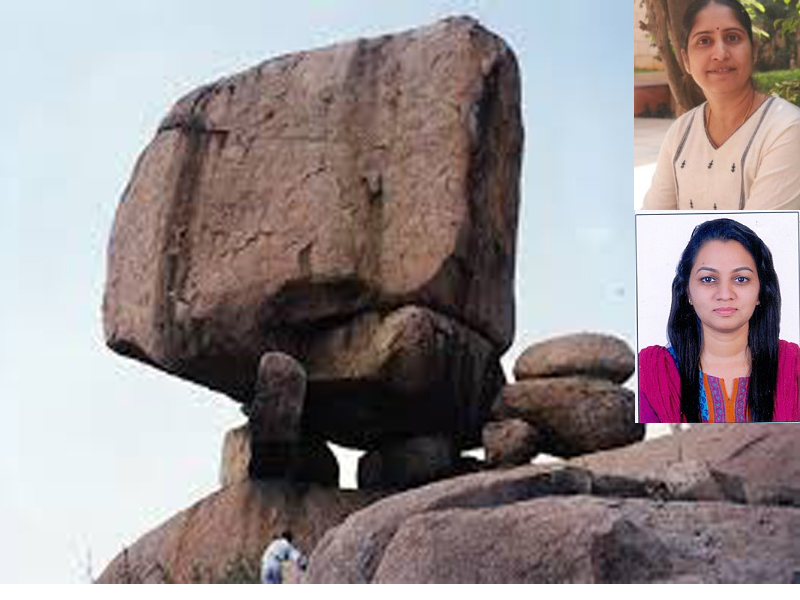

The rock structures in Hyderabad most of them dating back to billions of years are slowly disappearing in Hyderabad to…

The rock structures in Hyderabad most of them dating back to billions of years are slowly disappearing in Hyderabad to make way for real estate projects and infrastructure development. The sight of the massive rocks at the Nehru ORR once part of the city’s unique landscape, rolled down and destructed reflects the state’s failure to discharge the responsibility of protecting them in its capacity as public trustees of the natural entities.

The Telangana Heritage (Protection, Preservation, Conservation and Maintenance) Act, 2017, obligates the state to protect the heritage of Telangana. The Act defines natural heritage to include geological formations having outstanding value. It also constitutes a State Heritage Authority to notify heritage precincts. However, since there are no robust geological classification procedures, comprehensive listing mechanisms or enforceable conservation protocols under this law the hillocks remain unprotected. The unique rock formations in Khajaguda, the mushroom rocks around Kokapet, Rajendra Nagar, Banjara Hills are destructed. Deletion of Regulation 13 Hyderabad Urban Development Authority Zoning Regulations 1981 that provided legal protection to rock precincts prior to the introduction of Telangana Heritage Act, 2017 also amplified large scale destruction.

The litigations before the National Green Tribunal and High Court largely looked at the regulatory lapses and the aftermath of pollution from the crushing units and failed to assess these rock formations as a subject matter of rights. Despite the commendable work of NGOs like ‘Society for Rocks’ in raising awareness and listing rock formations, the destruction is widespread mainly because of the deregulation as a result of the deletion of Regulation 13 of Hyderabad Urban Development Authority Zoning Regulations 1981.

This gap reflects a deeper flaw in Indian environmental jurisprudence which is largely anthropocentric. The constitution considers environmental protection as a duty of every individual and judicial interpretations flow from the expansive definition of Article 21 through the integration of Sustainable Development doctrines. Most judgments remain human centric mandating guarantee of public health, pollution free air and water, sustainable resource use for the welfare of the people and not at the inherent rights of natural entities to remain free from pollution or destruction.

Contrast to this position, in 1972, a legal scholar Christopher D. Stone who ignited global discourse on the moral and legal rights of nature asked a radical question Should trees have standing? If artificial persons like corporations are given a status why can’t natural entities be given legal rights? His proposition led to the recognition of Rights of Nature concept in the Eco centric movement which recognises nature as having intrinsic value and as a subject of rights in contrast to the human centric approach in the sustainable development agenda.

This eco centric shift is in vogue in countries like Ecuador where the Constitution grants ‘Rights of Nature’ to Pachmama (Mother Earth), protecting nature’s right to existence and evolution. Similarly, Bolivian legal frameworks recognise Mother Earth as a collective subject of public interest with inherent rights. New Zealand has granted legal personality to Te Urewa Forest and Whanganui River. These legal developments were deeply rooted in indigenous cosmology and are a reaction to the exploitative government politics.

Such an eco-centric approach has profound importance in India, homeland to Hindu, Buddhist, Jainist traditions that has given greater emphasis to the human nature interconnectedness. The concepts like ‘Rta’, ‘Dharma’ and ‘vasudaiva kudumbakom’ presents a cosmic order that encompasses all forms of life on earth.

Indian Courts have echoed this philosophy in a few judgments such as the T.N. Godavarman Tirumulpad (2012) which expressed the need to shift from anthropocentric to eco centric principles in environmental conservation, and the cases like Centre for Environmental Law, WWF I (2013) and Ranjith Singh case (2024) reflected species centric reasoning within the eco centric frameworks. The judgment in Mohammed Salim (2017) declared river Ganga and Yamuna as legal persons as a step towards recognising nature’s rights.

The destruction of Hyderabad’s rock structures deserves urgent attention. In the current situation recognising them only as mere historical sites are inadequate. For the protection of these monolithic structures community custodianship model must be followed, keeping state as the trustee. There must be mandatory impact assessments and natural resource accounting as they act as natural aquifers, erosion barriers and climate archives.

The philosophy of Aldo Leopold, Land Ethic (1949) describes ecological ethics as an ecological necessity and eco centrism provides that ethical limitation on freedom of action in the struggle for existence that world is witnessing today.

To protect these natural entities, we must consider them as having inherent worth, afford them with legal standing and protect them from commodification. A lack of environmental consciousness can lead to irreversibility but these hillocks does not belong to anybody, they are the monuments of a bygone era to be made available for the future generations to come.

Authors

Dr Radhika Nidumolu

Dr. Sanu Rani Paul

Assistant Professors at Symbiosis Law School Hyderabad